Class 1: From Excel to Stata

A first approximation: Stata as an enhanced Excel

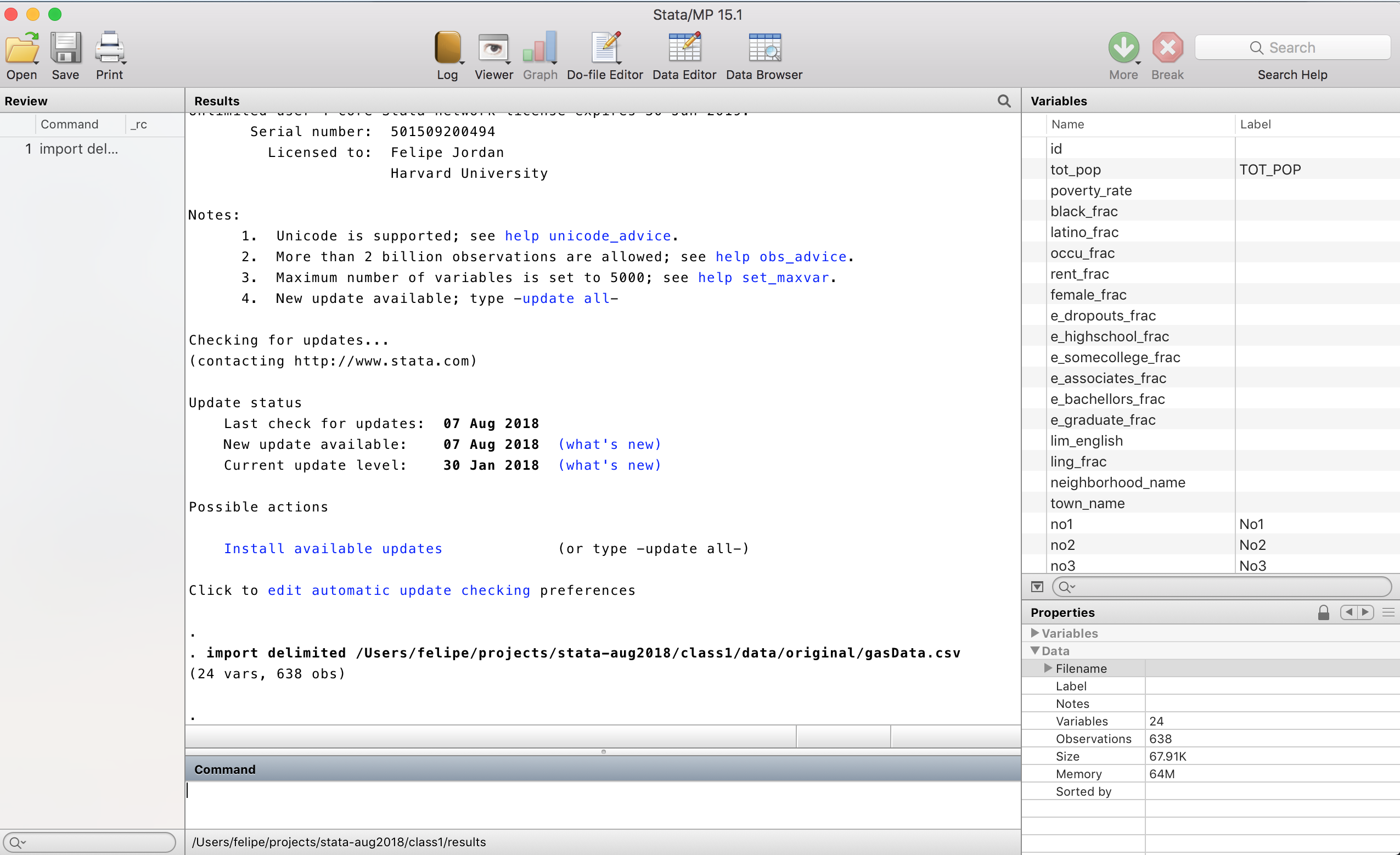

Open Stata. Four windows organized as a consolidated workspace will automatically pop up. Nothing seems too interesting—there is only a welcome message in the Results window with some information about our version and license.

To have some action, we need to load a database. All of the windows in this workspace are instances that either:

- Can give instructions to Stata to do something (Command window), or

- Show you the output of the instructions you gave (rest of the windows).

In most cases, the things we want to do are only meaningful when there is a database loaded. So let’s load our first database to have some action!

First, download and unzip the materials for this class. Select File > Import > Text Data from the top menu and browse for the file data/original/gasData.csv in the folder of this class. Click OK.

Now Stata has loaded a database. Double-click the file to inspect it in Excel (do not save afterwards!). As is generally the case in Excel, Stata follows the convention that each row represents an observation and each column a variable. In this case, observations are all the census block groups of Boston and Cambridge, and variables are some demographics from the 2010 Census and data on the status of gas leaks reported by utility companies in 2016 (more on the data later).

After loading the database, some of our windows have been populated with information:

-

The Review window (left) shows the history of the commands we have given to Stata in the current session (since the last time we opened it). There is one command now, which is the result of loading the database. Whenever you give an instruction to Stata using the top menu, Stata automatically picks the relevant command and runs it in the command line.

- The Variables window (top right) lists the variables of the loaded database.

- The Properties window (bottom right) shows some information about the loaded database.

- The Results window (top center) prints the result of the instructions we have provided. In this case, it prints the import command and gives us some useful information about the result.

- The Command window is where we can give instructions to Stata using commands.

A bare Stata window.

We have already indirectly introduced our first command when we imported the data (well, Stata did it for us). Now, type the following command in the Command window:

browse

There we go! We can inspect our database. Try ordering the data by different columns (right-click on a column).

Exit the Data Editor window. Now you can see that your Review window is populated with commands! Click on one of the commands that ordered the database. The command is now written into your Command window. Try editing it to sort by another variable and type browse again to see what happens. The database should now be ordered by that variable!

We will now give Stata some commands to obtain useful information about our database. This will be our first in-class exercise.

Exercise 1: Preparing a meeting in a hurry

Assignment

Suppose you work as a policy expert in an environmental NGO that advocates for fixing gas leaks in the Greater Boston Area (such as HEET). You have received the GasData.csv database from a colleague at 11:00 AM, and you have an important meeting with members of the Boston Public Health Commission at noon. Although in this very first meeting you did not expect to have data to share, showing them some aggregate figures about the extent of the gas leak problem in Boston and Cambridge would definitely be helpful to make future cooperation with their organization more likely. By answering these questions, you will make your point clear:

- What is the total number of leaks in each neighborhood?

- What is the average, standard deviation, minimum, and maximum number of leaks in block groups per town, when we only consider those with at least a hundred inhabitants?

- Is there a clear relation at the neighborhood level between the fraction of Latino population and the number of leaks per 10,000 inhabitants?

This is the email you received from your colleague:

Dear Colluegue:

After a week spent putting together the data from the Census, the American Community Survey, and the reports from the utility companies, I am happy to share with you this first version of the dataset.

You can check the definition of each variable in the file variables_description.csv, which is located in the same folder as the database. The gas leak data deserves some further explanation, though. As you know, utility companies classify leaks in three grades, from one (requires immediate repair because of safety concerns) to three (only requires monitoring). During 2016, some leaks were repaired and others were not. Hence, we have six types of leaks whose totals are reported in different columns in the database: yes1 (grade-1 leaks that were repaired), no1 (grade-1 leaks that were not repaired), yes2 (grade-2 leaks that were repaired), no2 (grade-2 leaks that were not repaired), yes3 (grade-3 leaks that were repaired), and no3 (grade-3 leaks that were not repaired).

I hope this information is useful for your meeting!

All the best,

Solution

Before starting, it is good practice to explore the database. Try the following commands:

describe

This command provides a brief overview of each variable, showing the name and the type of data (string, integer, float, etc.).

summarize

This command gives us more information for the numeric variables: the total number of non-missing observations and some summary statistics.

table neighborhood_name

This command gives us a frequency table for a variable.

Both describe and summarize can be followed by one or several variable names to restrict the output to those variables. If you want to know more about a command, the very first place you should ask is... Stata itself! Try:

help summarize

Stata will prompt a window with very useful information. It starts with the syntax of the command, something like:

summarize [varlist] [if] [in] [weight] [, options]

Not all commands follow this syntax, but it is pretty common. The command starts with the name of the command, followed by some arguments which may or may not be optional (they are optional if they are in square brackets). You can restrict attention to a subset of your database using the if and in qualifiers, and specify options after a comma to slightly modify the behavior of the command. Try:

summarize no3, d

Now Stata gives us more detailed information about unrepaired Grade-3 leaks (d is short for detail).

What if we are interested in seeing this summary only for Boston? Then we can use the [if] part of the command as follows:

summarize no3 if town_name=="Boston", d

Note the structure of what follows the if: it is a logical test.

We are asking whether town_name (which is a string variable) is equal to a specific value. “Boston” is enclosed in quotes because that is how Stata knows you are referring to a specific string value, and not something else (such as another variable in your dataset).

Ok, now we will start to prepare for our meeting. We will open a log file.

This file will save all the results shown in the Results window into a separate file.

To do this, go to File > Log > Begin... and create a log file named

exercise1 in the results folder of our class. As you might have

expected at this point, Stata just printed the relevant command into the Command window and

pressed Enter for us.

Now, type these commands one by one in the Command window to achieve our first goal:

display "The results that follow show what is the total number of leaks in each Neighborhood in Boston and Cambridge"

This command simply prints to the Results window (and hence to the log file) whatever you write between quotes. You can use it to make your log file more readable.

gen total_leaks = no1 + no2 + no3 + yes1 + yes2 + yes3

This command generates a new variable and sets it equal to the sum of all leaks. Once a variable has been generated, you cannot generate another one with the same name. If you want to replace the value stored in a variable that already exists, you should use the replace command. Try to give your variables names that are short to type but descriptive of what they contain. Variable names cannot start with numbers, are case-sensitive, and cannot contain spaces or special characters such as hyphens, parentheses, or quotation marks (underscores are allowed).

preserve

This command tells Stata to save a snapshot of the current state of the database. It is useful when we want to make a temporary transformation to achieve an intermediate goal but would like to return to the original version later.

collapse (sum) total_leaks, by(neighborhood_name)

This command tells Stata to create a new database where each row is the sum of the total_leaks variable for each neighborhood.

list

This command prints the current version of the database to the console.

restore

This command restores the database to the state it was in when we entered the preserve command.

log close

This command closes the log file (stopping the recording). We could have done this through the top menu as well.

Ok, we are done with the first question. Open your log file to verify that all this effort is safely saved in a file that we can print for our meeting. We are ready to start with the second part. Type these commands:

log using path_to_log_file, append

We are telling Stata to open the log file we saved and append the new results at the end. You have to replace path_to_log_file with the path to the log file you previously created.

display "The results that follow show summary stats on the number of leaks in block groups in Boston and Cambridge, separately for each town."

bysort town: summarize(total_leaks) if tot_pop > 100

This is a very useful combination of commands. The part before the colon says that whatever follows the colon should be done for each group defined by the variable that follows bysort. The part after the colon asks Stata to summarize the total_leaks variable, only for observations with more than 100 inhabitants.

log close

We are left with the third part. There are many ways to assess whether there is a meaningful relationship. We could calculate correlations, run regressions, build a nice table, or create a plot. Of all of them, a plot is one of the most useful, as almost everyone can understand what it represents. You can create very fancy plots using Stata (see some inspiring examples here), but for now we will explore the most basic type of plot in Stata (don't worry—we’ll get to the fancy ones in Class 4). You’ll see that even if it’s not very beautiful, the simple plot is very helpful for exploring your data.

It’s time for you to put into practice what we have learned so far! Append to your log file a series of commands that print a simple plot with the share of Latinos on the x-axis and the per-capita number of leaks on the y-axis. To guide you, I'll provide you with a list of instructions you need to translate into Stata:

- Append your work to the log file.

- Create a variable that stores the number of Latinos per block group, using tot_pop and latino_frac.

- If you haven’t already done it in the previous exercise, create a variable that counts the total number of leaks per block group.

- Preserve and collapse your database to obtain a new version where the unit of observation is the neighborhood, and you have three variables: number of Latinos, total population, and number of leaks.

- Create two new variables: the fraction of Latinos and the number of leaks per 10,000 inhabitants.

- Plot the relationship between both variables using plot. Type help plot to learn how to use this command.

- Restore your database and close the log file.

log using path_to_log_file, append

display "The results that follow show a plot that relates the fraction of Latinos in a neighborhood with the number of leaks per 10,000 inhabitants"

gen latino = latino_frac * tot_pop

cap gen total_leaks = no1 + no2 + no3 + yes1 + yes2 + yes3

cap is a nice command that captures errors. If total_leaks already exists, it will not overwrite it and will not report an error.

preserve

collapse (sum) latino total_leaks tot_pop, by(neighborhood_name)

gen latino_frac = latino / tot_pop

Note that we can use the name latino_frac again because in the new database created after collapse, that name does not exist yet.

gen gas_leaks_per_10000 = 10000 * total_leaks / tot_pop

plot gas_leaks_per_10000 latino_frac

restore

log close

Taking reproducibility seriously: Your first do file

We will create a do file now. To a first approximation, a do file is simply a file where you stack Stata commands line by line. Although simple, using do files efficiently will have a huge impact on your productivity, the quality of your empirical work, and your accountability.

We will write our first do file through a second in-class exercise.

Exercise 2: Sharing your work with your colleague

Assignment

Congratulations! The members of the Boston Public Health Commission were astonished by how well prepared you were for your meeting and are looking forward to future cooperation with your NGO! After taking a well-deserved nap, you check your inbox and see a new email from your colleague:

Dear Colluegue:

I heard you did excellent in the meeting — congratulations! Would you mind sharing your do file in case I have to present similar results in the future?

All the best,

In the rush of preparing for the meeting, you forgot to write your commands in a do file — as you should always do — but don't panic, it's never too late. We will go step by step:

- Open a new do file by clicking the Do File Editor button at the top of the Stata workspace.

- Type clear all on the first line and save the do file in the

scriptsfolder located in the folder for this class. Name the file exercise2.do. The clear all command tells Stata to remove whatever database is currently loaded into memory. - Write a new line in the do file that declares the working directory:

- Write a new line in the do file to import the database as follows:

- Write a new line that opens a log file:

- Copy and paste into the do file, line by line, each of the commands you used to answer the three questions. Skip the commands that open or close log files, but remember to end your do file with log close to properly close the log file.

cd path_to_class1_folder

After entering this command, all file paths in the do file will be interpreted relative to the declared working directory. For example, if your working directory is /Users/Colluegue/class1 and you want to open a file located at /Users/Colluegue/class1/data/dataset.csv, you only need to type data/dataset.csv. What if the file you want is not a child of your working directory? You can either enter the full absolute path or use the double-dot notation to access a parent directory. For example, if the file is located at /Users/Colluegue/other_project/a_file.csv, you can refer to it as ../other_project/a_file.csv.

import delimited using "/data/original/gasData.csv"

In the solution, you’ll see that I used the command insheet using "/data/original/gasData.csv", c instead. That command also works, but it is deprecated. It's still important to understand it, as many Stata users continue to rely on it.

log using "/data/results/exercise1.smcl", replace

Note that we use the replace option to overwrite the file if it already exists.

Solution

You can download the solution to this exercise here (please try to solve the exercise by yourself before looking at the solution).

Congratulations! You have written your first do file. Now you can share your work with anyone who has Stata by giving them your Class 1 folder. All the other person needs to do to reproduce your analysis is change the working directory at the very beginning of the do file. This is why we prefer using relative paths to files after the working directory has been declared — it makes reproducibility easier.

Now, run the do file by clicking the icon in the upper right that says “Run.” There are four other ways to run a do file:

- You can also run only part of your code by selecting specific lines and clicking the same icon. This is extremely useful while you’re working on a do file. Note, however, that when you run only a portion of your code, you are generally not starting fresh (for example, the first line clear all is not run), and you may encounter an error if you run a line that generates a variable that has already been created.

- You can run the entire do file from the Command window using: do path_to_do_file

- You can run it from another do file using: do path_to_do_file. This is a great way to organize a large project into smaller steps and then bring everything together with a master do file that runs the full analysis. This is a good practice, as it increases the readability of your code.

- You can run it from the terminal using the Stata executable. This is an advanced technique that can be very helpful when combining multiple software tools in your workflow, or when running Stata on a server without a GUI.

From now on, all our work will be done in do files. In practice, you’ll still use the Command window to experiment and explore your data, but most of your work should be written in do files.

Before introducing the homework for this class, let me briefly highlight a few important points:

- Comment your code: Please take a look at the file exercise2-solution.do. Do you notice all those lines that start with

//or*, and that block at the beginning that starts with/*and ends with*/? Those are comments, and they are ignored by Stata when it reads the do file line by line. Why include lines that Stata doesn’t use? Because your code will also be read by humans — including your future self, who will thank you for leaving helpful notes. You can write one-line comments using either*or//, and multiline comments with/*to open and*/to close. It’s a good habit to start your code with a long comment that briefly explains what the code does, the required inputs, the expected outputs, the author, contact info, creation date, last update, and any other details you find useful. The more context, the better. - Debugging your code: When you write your first version of a do file and run it, it’s very likely things won’t go as expected — and that’s totally normal. Even experienced programmers rarely get everything right on the first try. Fortunately, Stata provides error messages that help you understand what went wrong. For example, if you try to generate a variable

xthat already exists, Stata will display something like:variable x already defined

r(100);

This short message is usually enough to figure things out. If the message is less clear, you can click on the blue error code to get more information.

- Finding help: Especially in the beginning, you won’t always know how to solve a problem or which command to use. In those cases, Generative AIs and search engines are your best friends! Often your search will lead you to the Statalist forum, the official Stata user forum. It’s a large and active community of users, and you’ll probably find that 95% of your early questions have already been answered there. For the other 5%, you might find answers elsewhere — or you can even ask a new question on the forum. Of course, you can also reach out to the teaching team — but try to figure it out yourself first. That’s the best way to learn.

Homework: A disparity analysis

You did such a great job in your meeting that, a couple of weeks later, the Boston Public Health Commission commissioned a report from your organization. The name of the project is "A disparity analysis of exposure to gas leaks and access to gas leak repairs in the Greater Boston Area", and you have been chosen as the most capable person for the task. You’ve received the following email from your director:

Dear Colluegue:

I have decided to assign you the report for the Boston Public Health Commission. As a first step, I want you to give me a table that shows, for each income quintile, the average number of leaks per 10,000 inhabitants and the average fraction of grade-1, grade-2, and grade-3 leaks that were repaired during 2016. The table should look something like this:

| Quintile | Average Number of Leaks per 10,000 inhabitants | Fraction of Grade-1 Leaks Repaired | Fraction of Grade-2 Leaks Fixed | Fraction of Grade-3 Leaks Fixed |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bottom 20% | ||||

| 20-40% | ||||

| 40-60% | ||||

| 60-80% | ||||

| Top 20% |

Please send me the table as a .dat file and an Excel sheet. Also attach your do file and log file.

All the best,

To complete this homework, you will need to use three new commands:

- xtile

- save

- export

Use the help command to learn how to use these.

You can download the solution to this homework here (please try to solve the homework by yourself before looking at the solution).